Techtris – Edward Snowden ten-year anniversary edition

Two failures and one success. Does it come out in the wash?

Welcome back to another edition of Techtris, the newsletter about technology, the internet, and how it all fits together.

Let me open with a brief apology: one thing I am learning as I write this is while I have no shortage of things to say, a strict weekly “expect it at X time on Y day” doesn’t work properly for me or my schedule. As a result, I’m playing with a change – for the next month or two we’re experimenting with “at least four issues every calendar month”. I hope that works for you all.

As ever, thoughts, feedback, leads and tips are always welcome, and please do consider an upgrade to paid – given the schedule change I’m going to delay putting up the paywall a little longer, but please do consider it a freemium product in the meantime and consider chipping in a little if you can.

On with the show!

“You’ll be back in a week”

This week marks ten years and one week since then-Guardian editor in chief Alan Rusbridger called me unexpectedly at 5pm on a Friday, asked if I was still at work and if I could pop into his office if so?

Having snuck out early for a sneaky pint with a few colleagues (who I will still allow to remain nameless), I covered by saying I had just left but could easily turn around if he wanted, confidently expecting to hear it could wait until Monday.

It couldn’t. US editor Janine Gibson and her deputy Stuart Millar had, I would soon learn, dispatched Glenn Greenwald and DC correspondent Ewen Macaskill to Hong Kong to meet a new source – Edward Snowden. They’d requested my presence to help out with the reporting and editing from New York. I might be over there for a week or two.

That was my introduction to the Snowden story. I was, in the end, out there for slightly over two years, racking up almost 200,000 air miles in the process – we did not trust any remote communications, so if you needed to talk to someone, you got on a plane – and working more hours than I had ever thought possible.

Through more than one lens, it is easy to view the story as a failure. But I think behind the obvious shortcomings there’s a narrative that points to broader success – which I’ll try to unpick here.

Snowden gave several clear stipulations about how he wanted the Guardian and Washington Post to use the material he handed over. It was not to be a free-for-all, gleaning interesting nuggets and reporting the material gathered by the agencies just because it made for a great news story.

Instead, he specified that his reason for leaking was the scale of mass surveillance and bulk collection – and whether that had become incompatible with human rights, including those to free expression and privacy.

Given the sensitivity of the material concerned, the Guardian fully accepted that requirement as part of its public interest considerations: is this valuable to a debate on the extent of surveillance, and does publishing it outweigh the risks of disclosure? Despite the repeated efforts to paint the Guardian as spilling secrets with gleeful abandon, this set us a very high bar.

Politically, at least during 2013, the response was a tale of two continents. In the US the contents of the revelations sparked public outcry, widespread supportive coverage, and led to a public address by Obama acknowledging some of the concerns as valid. US surveillance law was actually tightened up, when it came to bulk domestic records collection.

The UK, by contrast, was far more outraged by the fact of the Guardian publishing the stories than it was by their contents. Parliament, when it expressed any opinion on the Snowden leaks, generally opined on the Guardian, rather than the leaks.

Rusbridger had to address a Commons select committee. We had numerous hostile front pages about our conduct. One MP ran a spirited campaign to get me personally locked up. UK surveillance law has only got even more expansive and intrusive in the decade since.

Politically and in terms of new legislation, the Snowden revelations did not lead to the reset that those of us who worked on it had hoped for. Intelligence agencies are going to do what they do – snoop. And they have hardly desisted from that.

In the courts

Superficially, we can claim a number of victories in the courts thanks to the Snowden revelations. Multiple cases got up to the European Court of Human Rights, which then went on to decide against the UK. The problem is that these cases amounted to nothing – almost by the system’s very design.

The ECHR cannot review individual surveillance decisions. Instead, its role is to judge whether the legal recourse available to surveillance targets are sufficient and whether oversight is sufficiently independent.

The UK failed on these fronts in multiple cases, but in each instance had managed to reform its surveillance law by the time the cases – which take years to proceed to a decision – were handed down. This meant the government could accurately say that the verdict was moot and the deficiencies identified by the judges had already been addressed.

This meant that the new system would need a whole new fresh legal challenge – this time years later and without the insight provided by the Snowden documents, because the rules and the tools have changed since then. The tweaks to the law were often superficial on the regulatory and supervisory side, meaning that reform through the courts is just a game of whack-a-mole, in which those challenging the system are also blindfolded.

There were definitely victories as a result of the Snowden files – but if we are honest, they were hollow.

Big tech to the rescue?

If you are an advocate of a more limited security state, then this has probably been dismal reading so far. One of the frustrations of writing about mass surveillance or bulk collection has been that there has been very little evidence offered for why it’s needed or if it works – privacy advocates live in the same world as everyone else and want to be safe just as much as anyone else does.

Without fail, every major UK terror attack in the last decade has involved someone who was on the radar of the UK’s police and usually also the security services – but was a person who was deprioritised for targeted or human surveillance due to a lack of resources.

This does of course raise the question as to whether money would be better spent on targeted, human-led intelligence, with a scaling back of some of the bulk collection. How much of the US and UK’s approach is simply “because we can”? The government never tried to put a microphone in every home, office and pub – but now that it was technically possible to pick up casual communications, it was impossible to resist, and the law enabled it too.

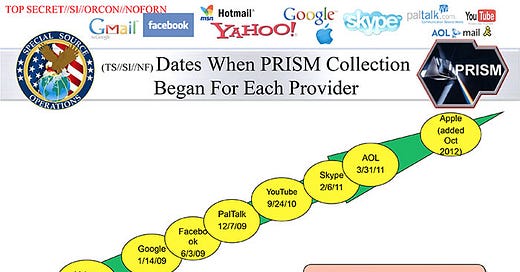

This is where the third pillar of the response to Snowden kicked in. It was big tech that was having its communications intercepted, its protocols undermined, its good faith cooperation over-extended (in the case of the PRISM programme).

There was a combination of genuine outrage at all levels of big tech coupled with a need to maintain the trust of global users that their data wasn’t out there and available for any government with access to the world’s network of fibre-optic cables.

That led to changes: US big tech markedly raised its security standards. Almost all web browsing is now secured through https, meaning lots of browsing metadata is now far more private as it flows across the network.

Most messaging apps now use end-to-end encryption, meaning big tech can’t access messaging history even if they are compelled to by law. Where once almost everyone’s private browsing and messaging travelled in the clear, it is now almost always encrypted.

This is scarily referred to as “going dark” and posited as a risk to our safety, but it is more a return of the pre-internet norm – most nations have gone through all of their history without anything like that kind of access to data, and those that relied on it tended towards the draconian. Few East Germans want to return to the era of the Stasi.

It’s safe in the dark

There is another odd consequence of US big tech getting its act together when it came to security and privacy – it might have ended up doing the US security state a massive favour.

The US has dominated the internet since its inception at every era of its development. It long styled itself as a benevolent overlord guiding the progress of the technology for the world – but Snowden gave the lie to that.

Not content with the huge economic advantage and benefits that hosting most of the major online companies offered, the US sought every intelligence benefit it could gain from that dominance too. Want data on someone in a European nation? No need to ask that nation for cooperation – just grab it from their US tech provider instead.

That dominance is now challenged and the US is unlikely to remain as the world’s only technological superpower for much longer. This can be seen in seconds by tracking even just the headlines about the US versus TikTok, Huawei, and others. There is fear about China in the digital ascendancy.

If the internet were as insecure today as it was in 2013, China could be set to exploit open data far more aggressively even than the USA did. Thanks to Snowden prompting tech to tighten security norms, there is much less available to them. Snowden may have handed the US security state – as well as regular global users – a sizeable strategic win.

It is easy to be blinkered, especially when your job is safety, but it is also the job of agencies to look beyond the horizon. It is arguable here that they missed – and were granted a lucky escape. That’s my view on a story in which I was proud (and remain proud) to have played a part. The US still portrays Snowden as an enemy of the state. I don’t think he ever was, and don’t think he is now – regardless of his circumstances.

There shall be more

This Snowden segment alone is just about as long as a regular newsletter, so I’m going to wrap it here – but do tune in next time for an assessment of whether billionaires are okay (spoiler: no), and a plethora of short-but-diverse VR and AR takes.

Until next time,

James

Techtris is written by James Ball and edited by Jasper Jackson, who probably still has thousands of classified files hidden on a USB stick somewhere.